We, as providers, see some infants navigate the differences between conventional bottle feeding and breastfeeding without any difficulty, but others struggle. We see choking, flooding of milk in the mouth and uncoordinated swallowing from some infants when they attempt to bottle feed. On the opposite side of the spectrum, we see some babies come to prefer the free-flowing, easy-to-feed from bottles so much that they struggle to go back to the breast.

Both these phenomena are forms of nipple preference (or, as providers previously termed it, "nipple confusion"). Nipple preference and even the possibility of nipple preference can be excessively stressful for parents and caregivers of infants. Whether it is the broken-hearted mother whose infant refuses to nurse again after bottle introduction or the captive nursing mother whose infant will not take a bottle, we have all seen these cases.

Where does nipple confusion originate?

The research around infant feeding1 is vast and at times contradictory. The main themes cited in scientific research as sources of feeding difficulties are artificial nipple properties, infant oral mechanics, infant suck-swallow-breathe patterns, and maternal-infant interactions. Most conventional bottle nipples are not designed to mimic natural nursing. They are typically made from silicone material nearly as hard as tire rubber, are hollow and have minimal stretch. Lacking softness, stretchiness and response to compression, the inherent property differences in the nipple material require that infants learn different feeding mechanics for bottle feeding.

The mechanics of sucking have been researched since 19582 and studies continue today. Researchers work with ultrasound and other imaging modalities to understand the intra-oral mechanics of both breast and bottle feeding.3, 4, 5 We are particularly interested in babies that go from breast to bottle to breast. Studies have gone back and forth regarding the impact of compression, vacuum and infant tongue movement (peristaltic vs piston/driving motions).

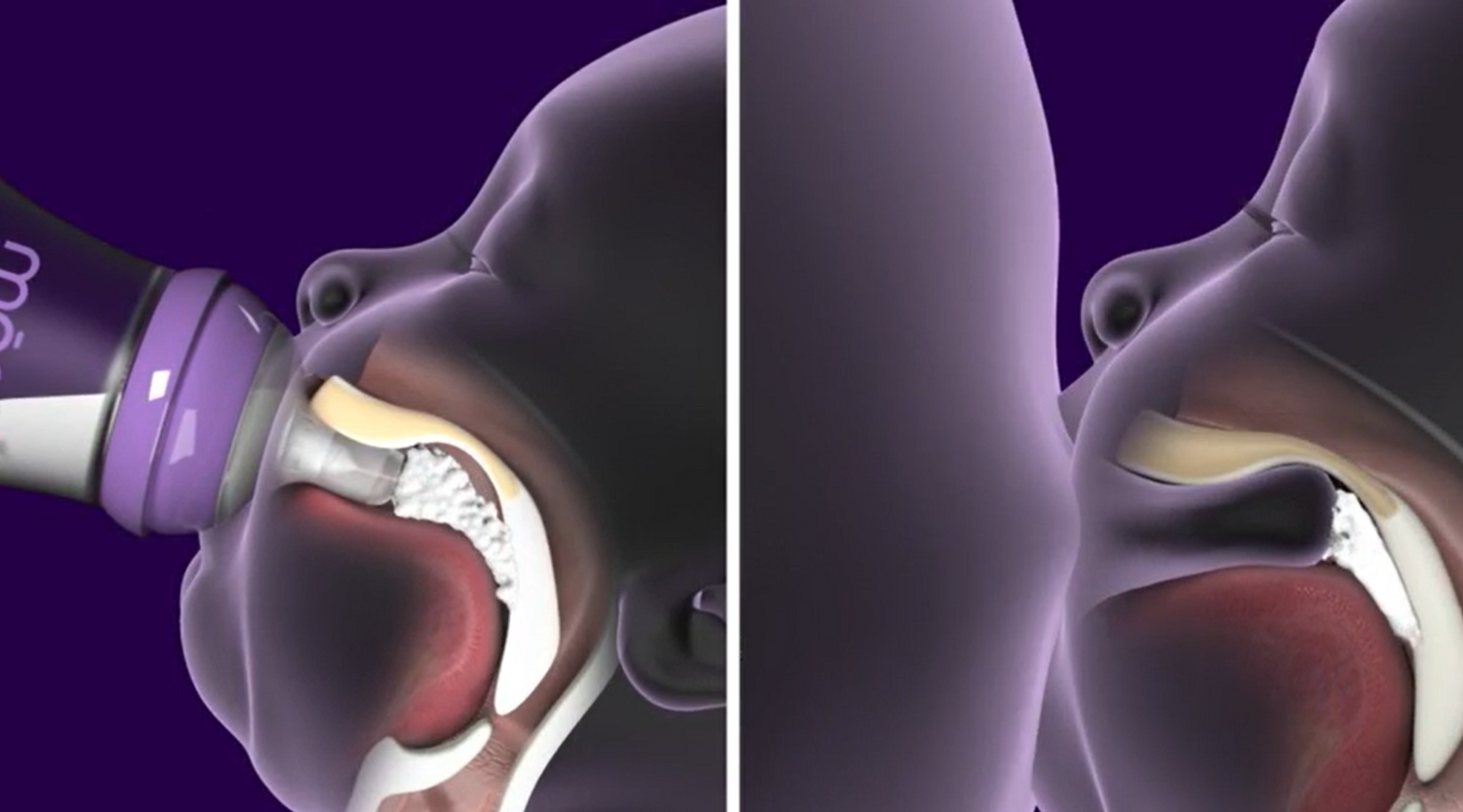

These studies highlight the material property differences in artificial nipple behavior during feeding. The hard silicone material of most conventional artificial nipples significantly limits stretch. The mōmi nipple is designed to mimic natural tissue mechanics. Its first-of-its-kind silicone composition creates a soft, solid nipple with a central milk duct. The mōmi nipple responds to both vacuum suction and compression shutoff, replicating natural nursing.

Natural feeding regulation and infant suck-swallow-breath patterns

Traditional bottle feeding shifts control of volume, timing, and pace of feeding from the infant to the caregiver. This is not how nature intended and does not follow the natural rhythm of feeding. Without the ability to self-regulate, infants become passive participants in bottle feedings.7 Allowing baby to self-regulate is critical to maintaining the natural rhythm of feeding, and helps prevent overfeeding, spit-up, and other negative effects. Nursing requires an active, engaged infant. Some pediatricians and caregivers have even referred to nursing as exercise. During nursing, babies are able to self-regulate their feedings, stopping on their own when full.8

The mōmi nipple allows the baby to stop the flow by compressing the nipple, just as in natural nursing. This enables the natural suck-swallow-breathe feeding rhythm, giving control of feeding back to the infant.

cited studies

- Fowler, Catherine, Christina Hourigan, Judith Kotowski, and Fiona Orr. “Bottle-feeding an infant feeding modality: An integrative literature review,” Maternal & Child Nutrition 16, no 2 (April 2020): 1-20. doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12939

- Adran, G.M., F. H. Kemp, and J. Lind. “A Cineradiographic Study of Bottle Feeding,” The British Journal of Radiology 31, no 361 (2014). doi.org/10.1259/0007-1285-31-361-11.

- Bolibar, Ignasi, Cristina Martínez-Barba, Angel Moral, Jose Ríos, Gloria Sebastiá, Gloria Seguranyes, and Josep M Ustrell. “Mechanics of sucking: comparison between bottle feeding and breastfeeding.” BMC Pediatrics 10, 6 (2010): 1-8. doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-10-6

- Itabashi, K., K. Mizuno, M. Taki, and Y. Segami.”Perioral movements and sucking pattern during bottle feeding with a novel, experimental teat are similar to breastfeeding.” Journal of Perinatology 33 (2013): 319-323. doi.org/10.1038/jp.2012.113

- Lagarde, M.L.J., J.L.M. van Doorn, G. Weijers, C.E. Erasmus, N. van Alfen, and L. van den Engel-Hoek. “Tongue Movements and Teat Compression during Bottle Feeding: A Pilot Study of a Quantitative Ultrasound Approach.” Early Human Development 159 (2021): 1–9. doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2021.105399.

- Erenberg, Allen, Arthur J. Nowak, and Wilbur L. Smith. “Imaging Evaluation of Artificial Nipples during Bottle Feeding.” Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 148, no. 1 (1994): 40-42. doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1994.02170010042008.

- Crow, Rosemary, Josephine Fawcet, and Peter Wright. “Maternal behavior during breast- and bottle-feeding.” Journal of Behavioral Medicine 3 (1980). doi.org/10.1007/BF00845051

- Crow, Rosemary, Josephine Fawcet, and Peter Wright. “The development of differences in the feeding behaviour of bottle and breast fed human infants from birth to two months.” Behavioral Processes 5, no 1 (1980) 1-20. doi.org/10.1016/0376-6357(80)90045-5

Other publications for consideration

Fleming, Kate M., Valerie Fleming, Claire Maxwell, and Lorna Porcellato.” UK mothers’ experiences of bottle refusal by their breastfed baby.” Maternal & Child Nutrition 16, no 4 (2020). doi.org/10.1016/0376-6357(80)90045-5